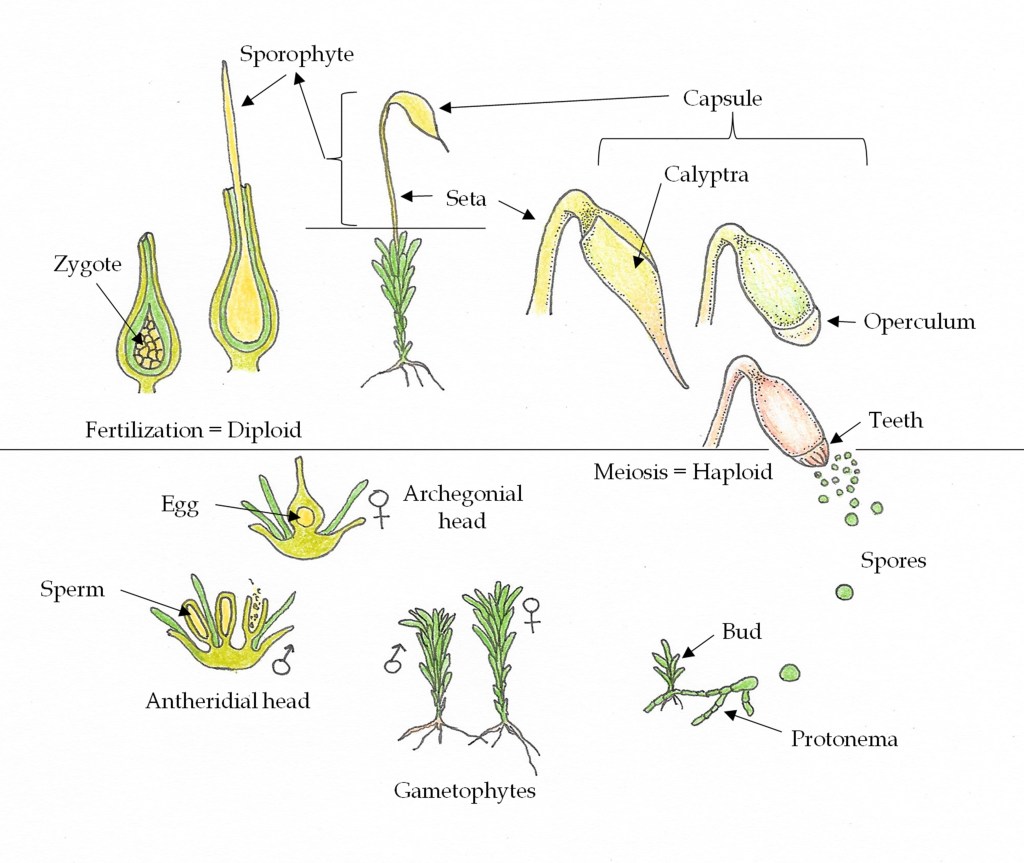

Like all bryophytes, moss has two stages of life: a dominant gametophyte stage, and a short-lived sporophyte stage. The gametophyte stage is haploid and is what we see most often out in the field. It consists primarily of a stem with rhizoids, and leaves that spirally radiate off of the stem.

Gametophytes of Polytrichum commune. Rhizoids are not visible in the photo, and just the stems and leaves are seen here.

The short-lived sporophyte stage is a result of successful fertilization between an egg and a sperm and is therefore diploid. It is the offspring of the parental gametophyte(s) and will stay permanently attached to the gametophyte until either the whole plant dies (an annual species), or just the sporophyte withers away leaving the gametophyte to continue on with its life (a perennial species). The sporophyte consists of a seta that may be of various lengths, and a capsule that may be of various shapes. Its function is to produce haploid spores that will blow away to start a new plant somewhere else.

A Polytrichum species with sporophytes.

Sexual Reproduction

Gametophytes will eventually produce an antheridial head which is male, and an archegonial head which is female. The antheridial head contains the antheridium which produce the sperm, and the archegonial head contains the archegonium which produces an egg. Plants may be dioicous (separate male and female plants) or monoicous (male and female reproductive organs found on the same plant). Within the monoicous group there are many different arrangements such as synoicous (male and female parts found together in same reproductive head) and autoicous (male and female reproductive parts found in different locations). See my post here on rhizautoicous or nannandrous mosses.

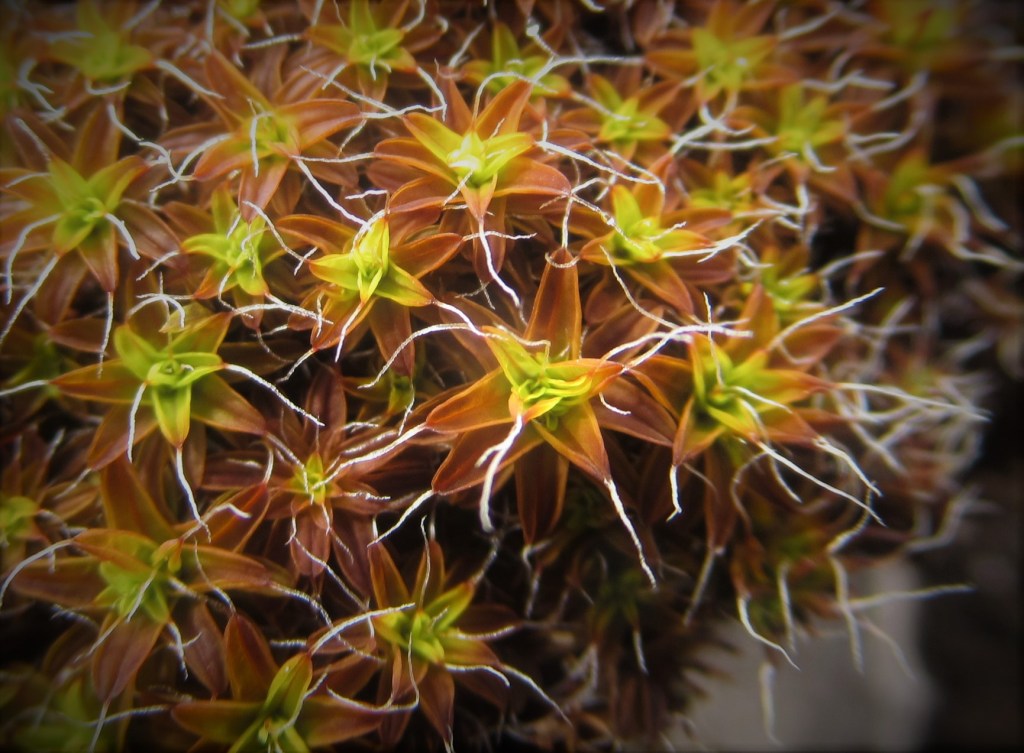

Polytrichum juniperinum is dioicous. In this genus, male gametophytes produce a flashy splash cup that resemble a flower. The red bracts are modified leaves that are designed to catch a raindrop and ricochet it away, thus distributing the sperm to more distant locations.

When successful fertilization of an egg occurs, a diploid zygote is formed. Eventually the sporophyte is formed, and haploid spores will be produced in the capsule. When the spores blow away and land elsewhere, if the conditions are right, they will begin to produce protonema. This is a matrix of threadlike single cell thick strands that spread over the substrate. A small bud(s) will form which eventually grows into the rhizoids, stem and leaves. In most species, the protonema is short lived and dies back once the stem and leaves are fully formed. In other species, the protonema mat is persistent and looks like green algae covering the substrate.

Ephemerum species have a consistent protonema mat, but the entire life cycle is short lived as the plants are ephemeral. The gametophyte is tiny, and only the brown capsule is barely conspicuous in this photo and looks like a grain of sand.

Diagram of a Moss Life Cycle

Gametophyte Morphology

Gametophytes consist of the protonema (which may or may not be persistant) the rhizoids, the stem, and the leaves. Plants may be upright or may sprawl across the substrate. Some species have no or limited branching, while other species may have irregular to 3-pinnate branching.

Above left: Climacium americanum is an upright moss that also exhibits a dendroid characteristic. Its upright stem is a stipe with small, scalelike leaves, while the branches have pronounced leaves and radiate outwards at the top. Above middle: Brachythecium rivulare ambles over its substrate and is regularly to irregularly branched. Top right: Thuidium delicatulum resembles a fern with its 2-3 pinnate branching which gives it its common name, delicate fern moss.

Rhizoids

Rhizoids are multicellular but are only one cell wide. Their main function is to anchor the moss to its substrate. They can play a role in moving water to the stem. Rhizoids come in many colors from clear, to reds and browns, to even purple. They can be smooth, or they can be papillose. If rhizoids go up the stem and form a thick fuzz that covers the stem, they are called tomentum.

The purplish-brown rhizoids of Leptobryum pyriform.

Extremely thick white tomentum coats the stems of Dicranum polysetum. Tomentum can be white to reddish-browns.

Stems

Several species will have paraphyllia on the stems which can be foliose (leaf like) or filamentous. Sometimes they are thick enough that they are easily seen with a hand lens. They are different than rhizoids because they contain chlorophyll, thus adding to the plant’s overall ability to photosynthesize.

Above left: Thuidium delicatulum stems are fuzzy due to the numerous filamentous paraphyllia. Above middle: A 1000x view of a Thuidium sp. paraphyllia. Above right: 100x view of the filamentous paraphyllia on the stems of Elodium paludosum.

While stems are typically green, they can be browns and reds.

The vibrant red stems of Pleurozium shreberi.

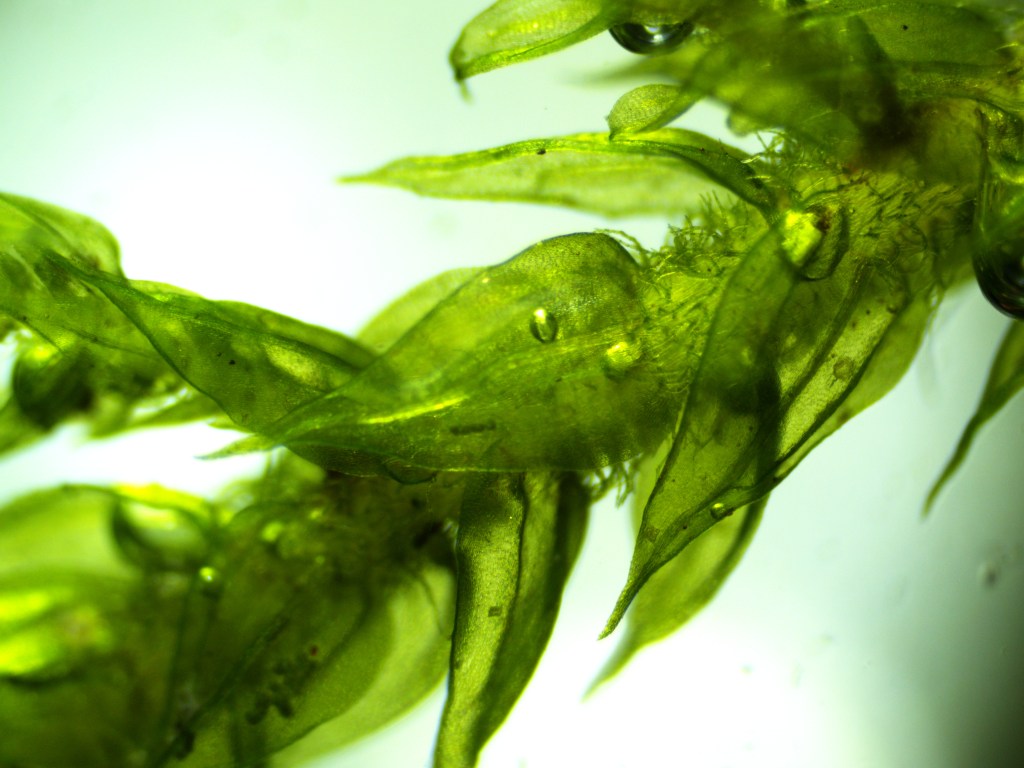

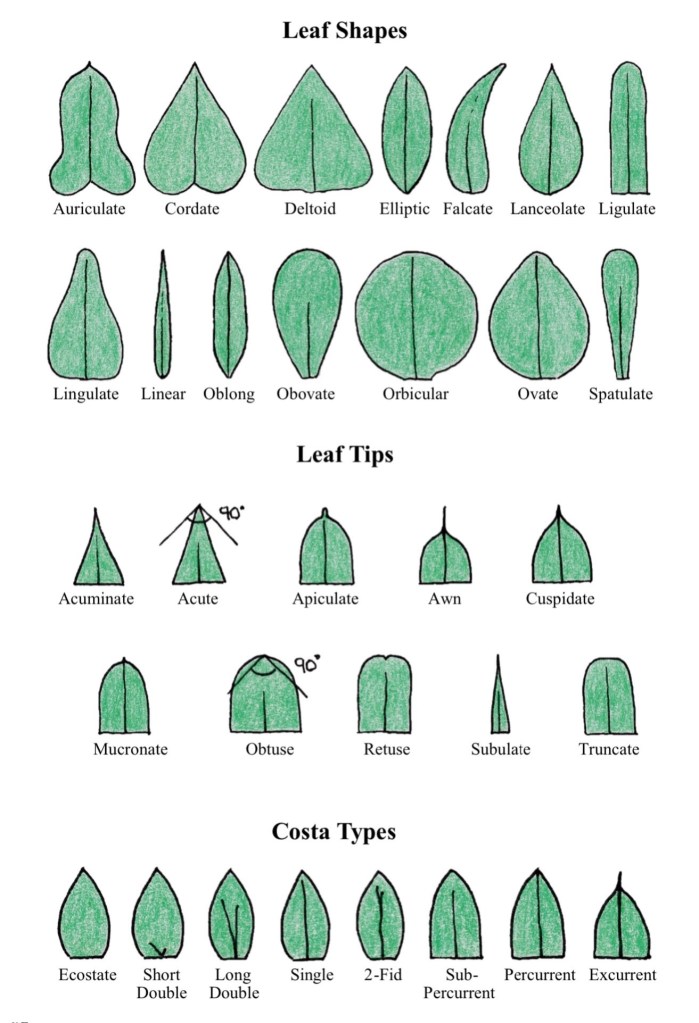

Leaves

Leaves come in many shapes and sizes. The only shape you won’t find in species in Missouri or in the United States are highly bisected leaves. Leaf tips are also various ranging from rounded to pointed. Additionally, some species may have a costa running down the center of the leaf. The costa is several cells thick and may help in transporting nutrients, and it can also add strength to the leaf itself.

Leaves can change colors during different times of the year. In winter many species may take on a yellow or brown hue, while others may become more red. Dry mosses may appear darker, almost black, but when moistened their vibrant green color will appear. And speaking of dry mosses, many species will have shriveled up looking leaves when dry, but they will burst open like an inflatable mattress when they become moist!

Above left: Syntrichia ruralis looks almost black when it is dry, but the gorgeous hyaline awns really stand out. Above middle: Syntrichia ruralis after hydration. Above right: Close up of Syntrichia ruralis sporting its winter colors of yellows and oranges.

An Atrichum species shows its curled up and contorted dry stage leaves on the right, and its moist stage with almost fully inflated leaves on the left.

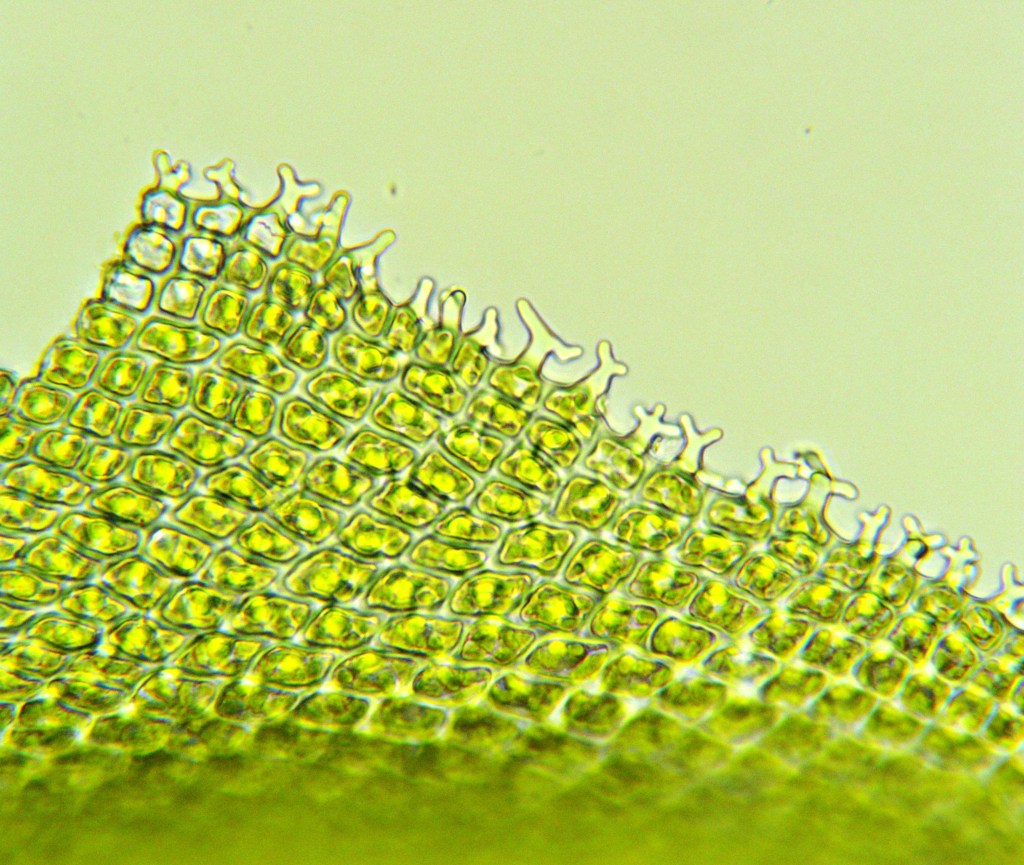

Leaves can also have accoutrements. They may have lamellar strips running down the length of the costa such as in the Atrichum and Polytrichum species. They can have teeth adorning their edges. They can also have cilia which can give them a wispy appearance.

Above left: Lamellae strips running the length of the costa on an Atrichum species. Above middle: Plagiomnium ciliare sporting its long, sharp teeth. Its common name is saber toothed thyme moss. Above right: The leaves of Thelia asprella have cilia arising from the edges.

Cells

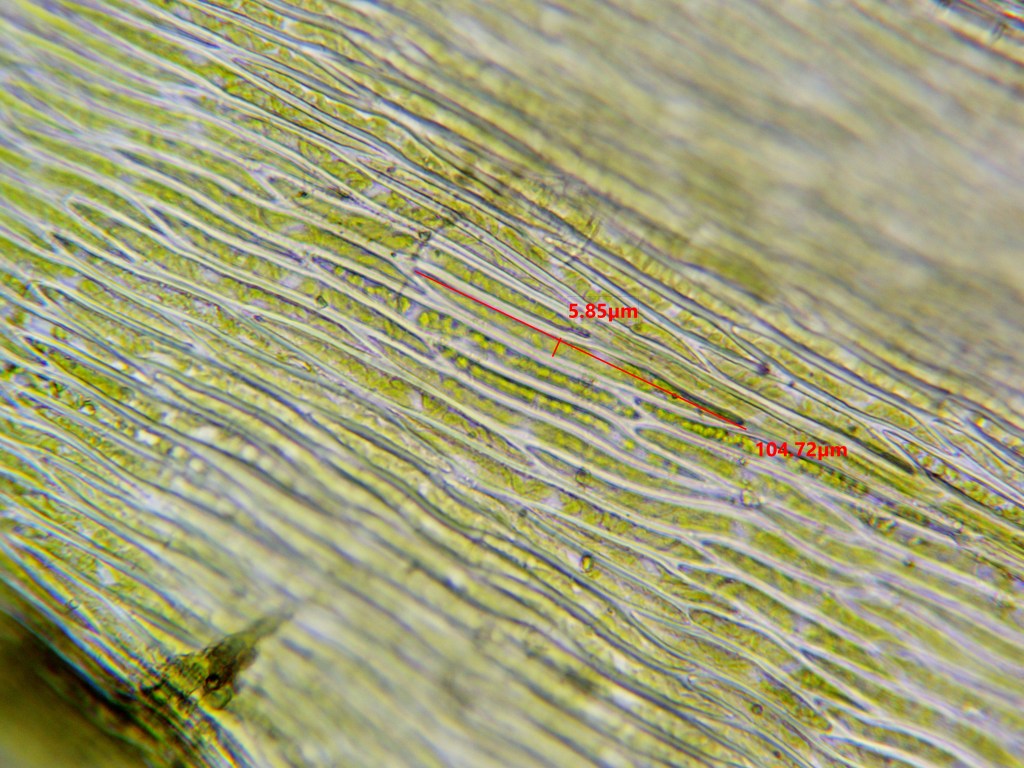

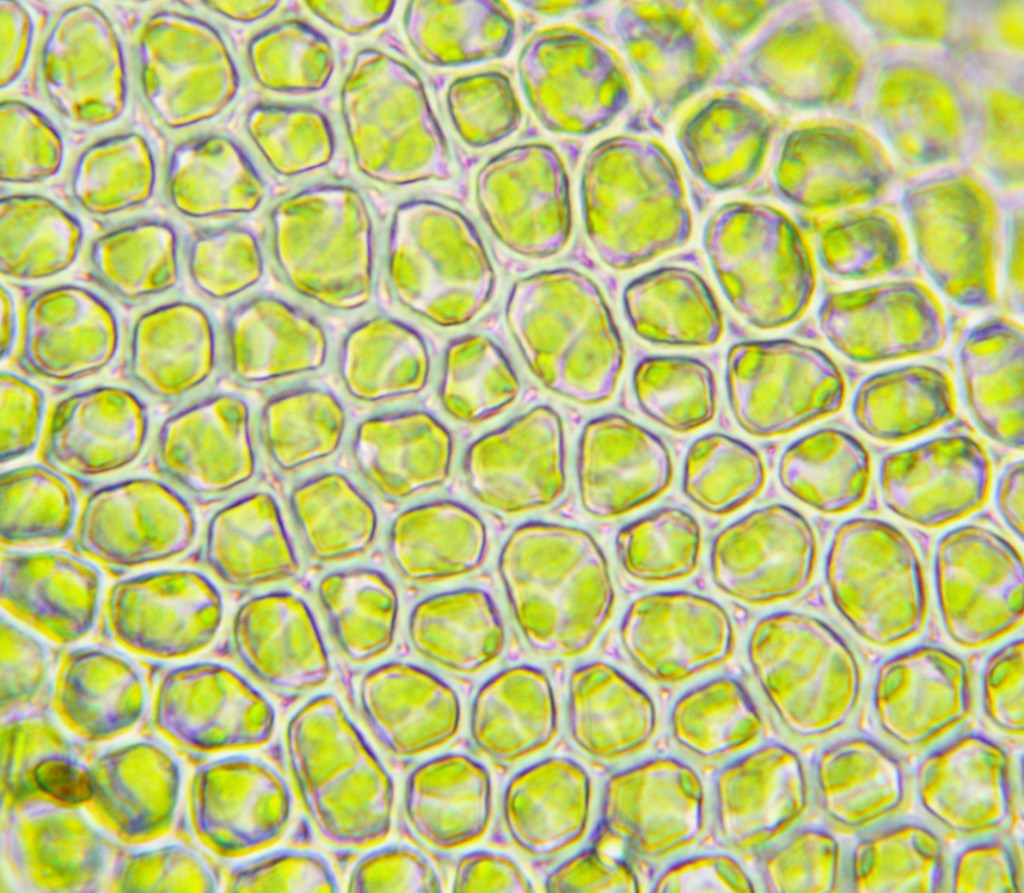

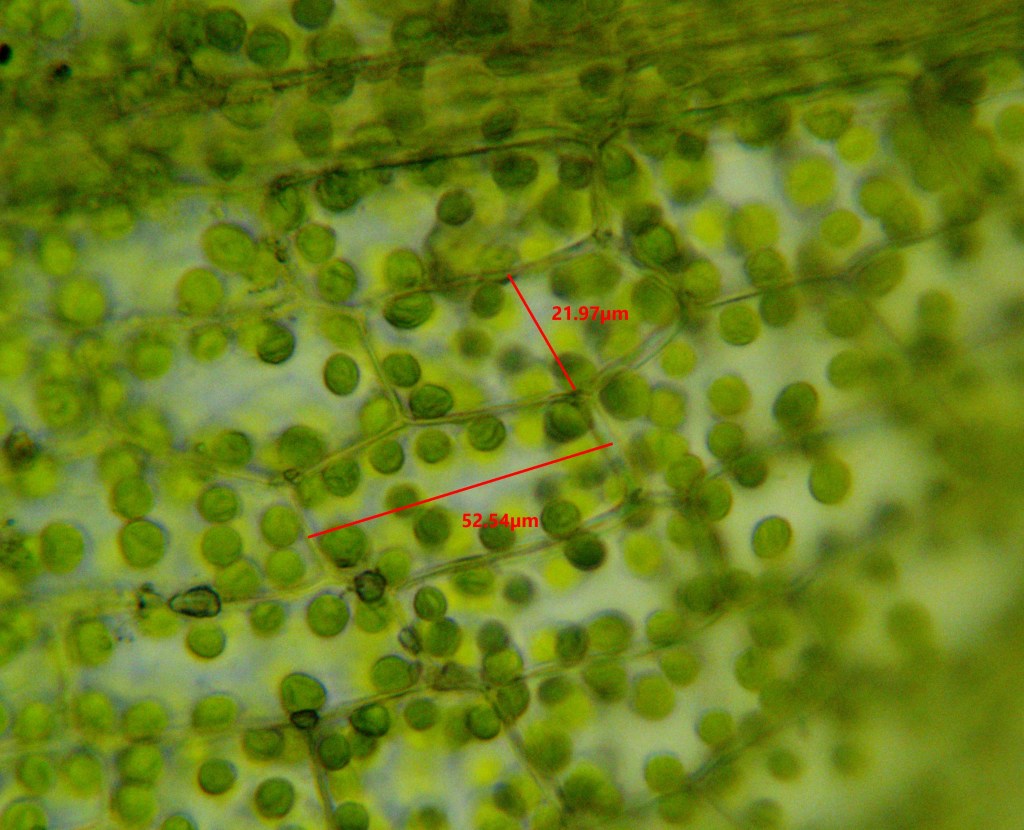

Cells range in sizes with some of the smallest being 5um in diameter, to longer ones up to 180um. Shapes can be squares, circular, hexagonal, and fusiform to name a few. Cell walls can be thin or thick, and they can be incrassate and porose. Most cells contain chlorophyll, and the number of chloroplasts per cell varies. Some species such as Sphagnum also have hyaline cells which lack chlorophyll, and their main function is to store water.

Above left: Long linear or fusiform cells of Brachythecium laetum. Above middle: rounded and thick-walled cells of Arrhenopterum heterostichum. The thick walls create a stellate appearance in the “corners” between the cells. Above right: Large blocky cells of Hygrometrica funaria with thin cell walls.

A cross section of Leucobryum glaucum which displays two types of cells. The green diamond shaped cells are the chlorocysts and contain chlorophyll. The clear cells are the halocysts which lack chlorophyll and store water.

Some cells have papillae which can be extravagant such as the branched papillae found on Thelia lescurii. Others may have just one small papilla per cell, while others may have many.

Sporophyte Morphology

Capsules can be exserted, whereby the seta is longer than the leaves and it is easily seen towering above the plant. In contrast, the capsules may be immersed whereby the capsule is buried within the leaves.

Above Left: Ditrichum pallidum produces tall, golden seta and is called golden thread moss. Above right: Pleuridium subulatum has immersed capsules that are buried in its leaves.

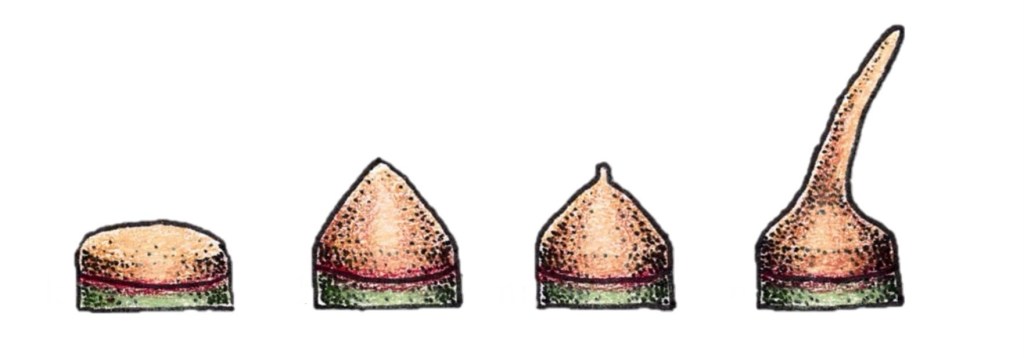

When a capsule is forming, it is protected by maternal tissue called a calyptra. Calyptrae come in two major shapes: cucullate and mitrate. It can be covered in hairs, or it can be naked. Some are large and cover most of the capsule, while others are small and merely sit at the top.

Cucullate calyptrae are split up the side. These are the sporophytes of Leucodon julaceous.

Mitrate calyptrae are not split up the side. They may have a solid bottom, or they may be lobed. These are the sporophytes of Ptychomitrium incurvum.

Above left: A Polytrichum species sports a cucullate calyptra that is covered in hairs. Above right: Schistidium viride has a tiny lobed mitrate calyptra that barely covers the top of the capsule.

When the calyptra falls off, one can clearly see the operculum at the top of the capsule, if there is one. The operculum can be viewed as a cap that will eventually fall off, allowing the spores to be released. The operculum comes in various shapes and styles.

From left to right: flat; conic; conic/apiculate; rostrate

After the operculum falls off, you might see what look like teeth. This is called the peristome. There can be two sets, with the outer set called the exostome, or simply teeth, and the inner set called the endostome, or segments. They can be various lengths and vary in numbers. The peristome can help regulate the release of the spores, with some species being able to open and close them with changes in humidity.

Above left: The teeth of an Atrichum species are curled shut. Above middle: The large teeth of a Schistidium species are reflexed wide open. Above right: The teeth of Tortella humilis are long and twisted around each other.

Some species such as Physcomitrium pyriform, lack a peristome. The capsule remains open to the environment and resembles an urn or wine goblet when mature.